ISSUE 2.3

welcome

issue contents

contributors

interviews

our editors

The poetry editors, Rappahannock Review: You’ve published poetry, nonfiction, and fiction—both long and short form. How do you approach writing in the different genres? Do you have a preferred genre to write?

Michael Colonnese: It’s true. I’ve published fiction—both short and novel length, nonfiction essays, both scholarly and personal, and poetry in both short lyrical and longer narrative forms. And actually, early in my career, before I ended up earning a paycheck as an English professor, I wrote TV commercials and lots of advertising copy. I once ghost-wrote an optimistic corporate report for the stockholders for a Fortune Five Hundred company that had actually experienced some huge financial losses, and that report was truly a work of imaginative fiction.

Over the years, I suppose I learned enough about craft and grammar to write and edit in any genre, and I’m a such a compulsive reader of contemporary literature that I know enough about what a poem or a short story or a novel should look like that I can usually coax whatever I’ve written toward some end. But that said, unless I’m writing something for commercial purposes, I often don’t know what form I’m working on until I see some words on a page. I once wrote a novel that began with a single image, and I’ve written poems that were the edited distillation of many pages of prose.

I’ve probably published more poetry than anything else, but that’s probably a consequence of a busy and sometimes disorganized life. It can take years for me to draft and edit a novel. The kind of effort it takes to write every day and to hold the entirety of something as long as a novel in my mind requires an emotional, physical, and financial stability that is hard won and often hard to sustain. Poetry, I’ve found, can sometimes be written and even edited in creative bursts—on the run as it were. I’ve sometimes written sentences that ultimately became published poems in notebooks and in longhand. My novels, short stories, and nonfiction essays were almost always first drafted on a computer.

RR: As a professor, how do you approach teaching Creative Writing?

MC: I’ve been teaching college Creative Writing courses for nearly thirty years, and on the first day of every semester I’m still filled with utter terror—as if I have nothing worth saying and no advice to give. And perhaps such terror isn’t necessarily a bad thing in that it suggests I’ve retained some sense of humility and understand how hard it is to write so much as single sincere word.

But then the workshop begins, and once we’ve all introduced ourselves and I’ve laid down some basic ground rules to foster trust and maintain civility (i.e. be specific about what you like and dislike and discuss the writing not the writer), I usually ask each student to identify an emotionally significant event by which he or she measures time, and to begin by writing a few pages of judgement-free description about that event that might allow someone who wasn’t there to see or hear what it was like.

Over the years I’ve discovered that there’s always a poem or a story to be discovered in such description, and that if one gets words on paper and is willing to edit what one writes, structure and meaning will find a way to surface. I think it was the poet Dick Hugo who said that it’s impossible to write meaningless sentences. In writing, as in psychoanalysis, it doesn’t so much matter where one begins so long as one begins, but one also needs a reason to spend the time necessary to sweat the details and learn one’s craft.

It sounds self-evident to say so, but students who want to write often need support and feedback from others in workshop to discover that their own experiences and responses have a fundamental importance.

RR: What inspired the poem “Those Birds”?

MC: Many years ago, I was living in NYC and working in Manhattan. It was late December, cold, wet, and overcast, and the trees in Central Park were bare and gray. It was a dark time in my life; I’d reached some sort of emotional end; I felt like a failure; I wanted out, and I didn’t know how I’d ever achieve anything. I sat on a park bench and watched a rather pathetic row of birds lined up on a phone wire, and I envied both the communal simplicity of their sorry existence and their ability to fly away. The poem began as a rather literal depiction that specific situation.

RR: In “Those Birds,” the minimalistic form used only emphasizes the strong imagery used throughout. What was prompted you to utilize this form?

MC: Well, as I wasn’t feeling much of anything at the time besides a kind of blank desperation, I knew the poem couldn’t and shouldn’t be effusive. So it started out short, and got shorter; I cut it back last year when I discovered it in an old computer when I was transferring some old files. The first draft was probably written thirty five years ago, but poems seldom go stale and nothing saved in memory is ever really lost.

RR: Every author has a different writing style and process when approaching a specific piece. For “Those Birds,” what writing techniques did you use to help establish this piece?

MC: Poems by other authors have always been my teachers, and I’ve never been too proud to borrow technique or even patterns of diction if I suspect these might improve something I’ve written. When writers read, writers appropriate. When I was editing “Those Birds” I was reading the great Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo and the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo. Both of them knew something about despair, and both are fabulous when it comes to compression. From their short clear, sincere, image-rich poems, I learned that one obviously doesn’t have to explain everything to imply a great deal more.

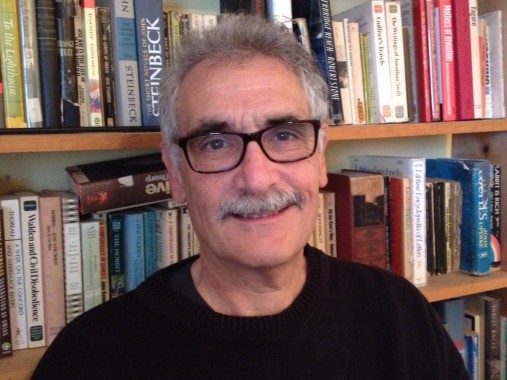

Michael Colonnese’s work in Issue 2.3: